Mistakes I Made Writing a Django App (and How I Fixed Them)

I recently announced the release of a project I’ve been working on for a few months. The project is called Lintly. It is a continuous Python code quality checking tool that lints your code when you push to GitHub. I won’t go into detail about what Lintly is here — you can read about that in the other blog post or go to lintly.com. Instead, I’d like to discuss my experience creating my first proper side project, some of the mistakes that I made writing it, and how I fixed the mistakes.

Technical Note: Lintly is a Django 1.9 application that runs on Python 2.7.

The Mistakes #

-

Mistake #1: Making functions do too much

-

Mistake #2: Using magic strings

-

Mistake #3: Putting third-party API calls everywhere

-

Mistake #4: Feature creep

-

Mistake #5: Comparing my app to others

Mistake #1: Making functions do too much #

My, how code can become a big bowl of spaghetti very quickly. And don’t get me wrong, I love a good bowl of spaghetti. But when it comes to code, I’m not a fan.

This mistake was mostly made out of laziness. I wrote functions that were too large, did too much, and knew about things they had no business knowing about. It turns out this trap is very easy to get into when you dive in coding without much planning. Let me give you an example.

The two methods below are a part of the Build class. A build occurs when Lintly pulls down code from GitHub, lints it, stores the results, and sends out notifications. Here’s how a Build linted a repo originally:

def lint_entire_project(self, local_repo_path):

"""Runs quality checks on the local repo and returns the output as a string."""

self.state = BUILD_RUNNING

self.save()

process = subprocess.Popen(['flake8', local_repo_path],

stdout=subprocess.PIPE,

stderr=subprocess.PIPE,

shell=False)

stdout, stderr = process.communicate()

return stdout

def parse_results(self, local_repo_path, raw_results):

"""Parses flake8 output into a dict of files with issues."""

results = raw_results.replace(local_repo_path, '')

file_issues = collections.defaultdict(list)

regex = re.compile(r'^(?P<path>.*):(?P<line>\d+):(?P<column>\d+): (?P<code>\w\d+) (?P<message>.*)$')

for line in results.strip().splitlines():

clean_line = line.strip()

match = regex.match(clean_line)

if not match:

continue

path = match.group('path')

result = {

'line': int(match.group('line')),

'column': int(match.group('column')),

'code': match.group('code'),

'message': match.group('message')

}

violations[path].append(result)

return violations

This is rough, and a clear violation of the Single Responsibility Principle, which states the following:

A class should have only one reason to change.

In this example, a Build does more than it should. It knows about the flake8 CLI and also parses the results of flake8. It should really hand all of this (linting + parsing) off to another class.

How I fixed the mistake #

I decided to create a new Linter class that would house the logic that could be shared between all linters. Builds could instantiate a linter and use that instead of doing the linting themselves.

Here was my second attempt:

def __init__(self):

self.linter = self.get_linter()

def lint_entire_project(self):

"""Lints the local repo and returns the violations found."""

self.state = BUILD_RUNNING

self.save()

violations = self.linter.lint()

return violations

Much better! A build is no longer running CLI tools on the command line and no longer parsing its own results. This is much more extensible as well, as the flake8 tool is no longer hard-coded into the build. It will be a lot easier to add linters in the future.

Mistake #2: Using magic strings #

Currently, Lintly only works with GitHub. In a future release, I plan to make Lintly work with other services like GitLab and BitBucket. That’s why URLs are in the form of /gh/dashboard/ or /gh/new/. The gh portion stands for GitHub. When you go to a page in Lintly, you go there in the context of an external Git service. That way the backend code knows which API tokens to use, which repos to show you, and which organizations to show you.

This is what the URL looks like:

url(r'^(?P<service>gh|dummy)/',

include('lintly.apps.projects.urls', namespace='projects')),

And here is how that maps to a view function:

@login_required

def dashboard(request, service):

projects = request.user.get_projects(service)

return render(request, 'project/dashboard.html', {'projects': projects})

That looks okay. The URL ensures that the service variable will only ever be gh or dummy (more on dummy later). In the future, I can add gl and bb so that URLs and views work with GitLab and BitBucket respectively.

The problem was in my templates. My templates would hard-code the gh variable all over the place. For example, here’s what a button would look like:

<a href="{% url "project:add_projects" "gh" %}" class="btn btn-primary">

<em class="icon-plus"></em> Add Projects

</a>

How I fixed the mistake #

To fix this I introduce a new service variable into all templates. This variable can be passed to URLs so that all URLs are relative to the current page’s service. I did this via a context processor:

# Future git services will go here

GITHUB = 'gh'

DUMMY = 'dummy'

def service(request):

services = (GITHUB, DUMMY)

the_service = None

for _service in services:

if request.path.startswith('/{}/'.format(_service)):

the_service = _service

return {'service': the_service}

Now when I need a URL, I simply pass along the service to the url template tag:

<a href="{% url "project:add_projects" service %}" class="btn btn-primary">

<em class="icon-plus"></em> Add Projects

</a>

Mistake #3: Putting third-party API calls everywhere #

Lintly uses several third-party APIs, the most important of which is the GitHub API.

I started out putting API calls directly in my views, models, and template tags. For example, here’s what the User.get_projects() method looked like originally:

def get_projects(self):

client = Github(self.access_token)

owner_logins = set(org.login for org in client.get_user().get_orgs())

owner_logins.add(self.username)

return Project.objects.filter(owner__login__in=owner_logins)

Notice that this creates a Github client object directly (the Github client comes from the great PyGithub library). Unfortunately, the get_projects method was called from the project sidebar (the sidebar on the left-hand side of each and every page while logged into Lintly). This meant I had to mock the get_projects method on every single view test…quite the nightmare!

How I fixed the mistake #

I made this change along with the change in Mistake #2. That’s right, the good ol’ service variable.

First, I refactored all interactions with GitHub into their own class: the GitHubBackend class. This is a simple wrapper around the PyGithub library. I also created a Stub object called DummyGitBackend that would simulate the interactions with an external Git service (like GitHub).

Now when I need to call an external service I get a GitBackend instance depending on the service. In production, service is always ‘gh’, which means we always use the GitHubBackend class to make API calls. In unit tests, service is always ‘dummy’, and the DummyGitBackend stub class is used. This ensures that my tests never call out to GitHub.

Here is the new implementation of User.get_projects():

# This dict lives in its own file

git_clients = {

GITHUB: GitHubBackend,

DUMMY: DummyGitBackend

}

def get_projects(self, service):

# Dynamic based on the service

GitBackend = git_clients[service]

git_client = GitBackend(user=self)

repo_full_names = [r.full_name for r in git_client.get_user_repos()]

projects = Project.objects.filter(full_name__in=repo_full_names, service=service)

return projects

Mistake #4: Feature creep #

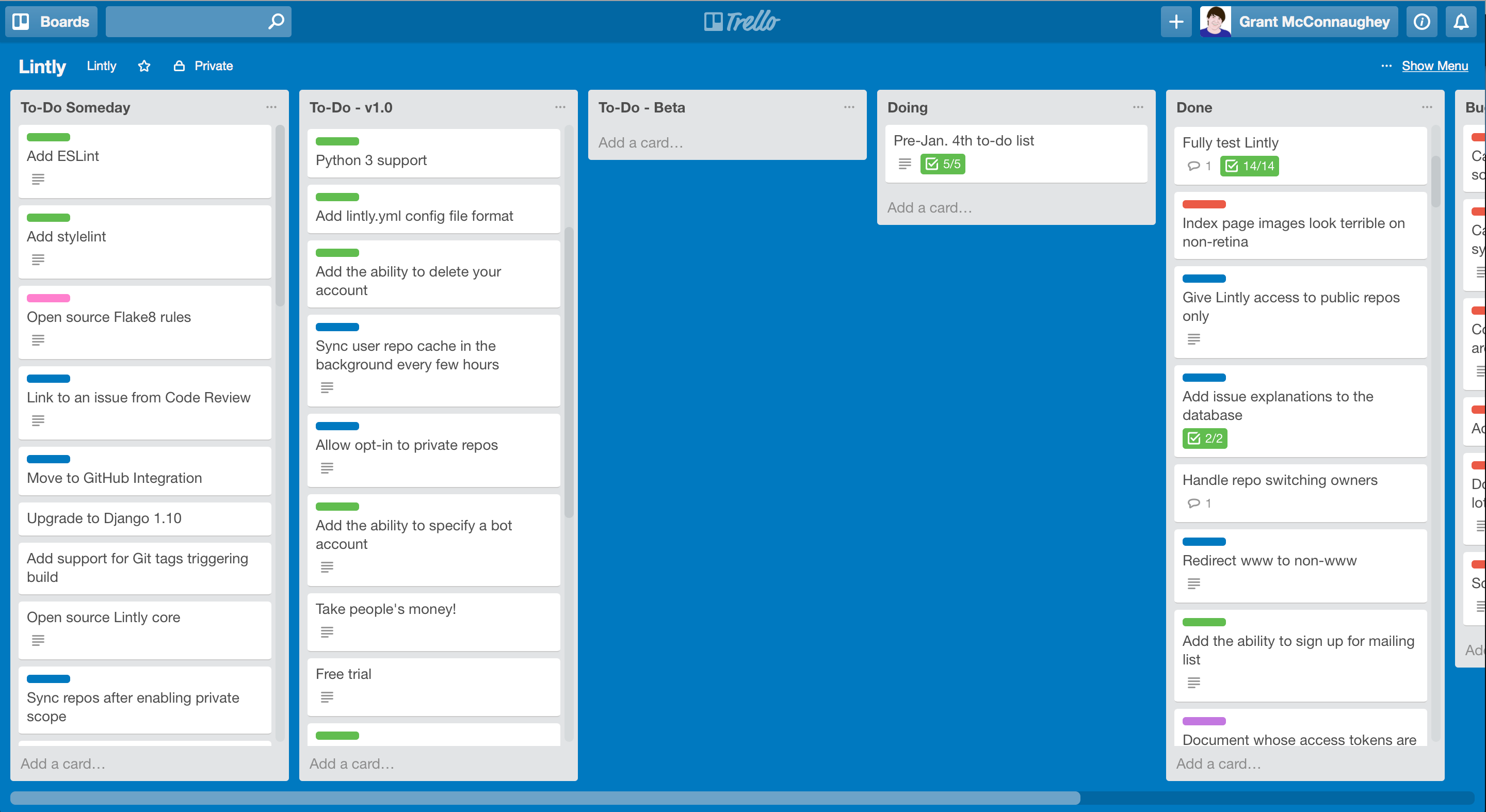

I love using Trello for simple project management. That’s why I used it for Lintly.

For Lintly, I have a Trello board with 4 columns:

- To-Do - v1.0

- To-Do - Beta

- Doing

- Done

My workflow was simple: pull cards from the Beta lane and move them into the Doing lane. When I finished the feature, I would commit the code and move the card from Doing to Done. When all items in Beta were finished, then the Beta was ready to release.

My trusty Trello board

My trusty Trello board

This sounds simple enough, right? The problem is how easy it is to move items from v1.0 to Beta. I would sometimes see a feature in the v1.0 lane and convince myself that I could easily throw that into the Beta as well. This may not seem like a big deal, but doing that over and over again ensured that I would miss my own personal deadlines to have the Lintly beta released.

How I fixed my mistake #

I created a second Trello board called “Lintly v1.0” and moved the To-Do - v1.0 lane over to that board. Just the simple act of making the lane harder to see on a daily basis meant that I was much less likely to move its cards over to the Beta.

Stay focused when you are working on a beta. Figure out which features are an absolute must and ignore all the rest until the beta is released.

Mistake #5: Comparing my app to others #

Unless you are creating an app that is based on an entirely original idea, you’ll probably find yourself making this same mistake. The mistake is comparing your app (and perhaps even yourself) to others.

I thought of the idea for Lintly in June while I was driving my wife and I home from our honeymoon. I broke international car-napping laws and woke my wife up to have her type a note on my phone. The note was four words: Flake8 As A Service.

At the time this seemed wholly original. I couldn’t believe that no one else had thought of this! We have sites like CodeCov that continuously check your code’s test coverage, so why not have the same for linting. I had to make this quickly.

As I started working on Lintly over the next month or two I realized that I was less original than I thought. There were other sites like Landscape, which lints Python, or HoundCI, which comments on GitHub PRs. This realization was certainly disappointing. Those apps are great and I feared I could never make anything as good as them. I stop working on Lintly for at a time due to discouragement.

How I fixed the mistake #

Finally, something clicked, and that something is what helped me push through and finally release Lintly. That was the realization of two things:

- Competition is a good thing

- Everyone needs a side project

There will almost certainly always be competition for an application you are making, and that is perfectly fine. All you can do is make the application the best that you can and enjoy working on it. And if nothing else, it will always look good on a resumé!

Conclusion #

Lintly isn’t perfect and it never will be. As you can see, I made lots of mistakes making it. But I also learned a lot about creating projects from start to (kind of) finish and about releasing them. It was a lot of fun to make and it will continue to be fun to work on as I add new features like Python 3 support and support for other linters.